This article discusses how as prisons try to block unauthorized cell phone use, companies are developing systems that cost over $1 million to address the problem. This is cost that will be passed on to the taxpayer if prisons adopt this technology. By adopting the meshDETECT secure prison cell phone solution, prisons and taxpayers will avoid this cost and reduce prison cell phone smuggling and the value of contraband prison cell phones.

This article discusses how as prisons try to block unauthorized cell phone use, companies are developing systems that cost over $1 million to address the problem. This is cost that will be passed on to the taxpayer if prisons adopt this technology. By adopting the meshDETECT secure prison cell phone solution, prisons and taxpayers will avoid this cost and reduce prison cell phone smuggling and the value of contraband prison cell phones.

The Bloods street gang is a known distributor. Charles Manson has had at least two. In April, one was used to start a riot in an Alabama prison. Much to the chagrin of corrections officials nationwide, inmates have discovered the advantages of using mobile phones to coordinate escapes, intimidate witnesses, and order retaliation against other prisoners.

Although there are no nationwide statistics, in California alone more than 10,000 contraband phones were confiscated from inmates in 2010, up from 1,400 in 2007. In Mississippi, authorities grabbed more than 4,000 handsets from prisoners last year, up 43 percent from 2009. “Illegal cell phones are probably the largest public-safety risk prisons are facing nationally,” says Terri McDonald, chief deputy secretary of California’s Corrections and Rehabilitation Dept.

Those worries have spurred nearly a dozen companies to develop electronic devices that jam signals, find phones, or block calls from unapproved numbers. “The only way to eliminate the threat is to physically capture the cell phone from the inmate,” says Terry Bittner, director of security products for ITT Defense & Information Solutions. The McLean (Va.) company makes a device called the Cell Hound that detects phone signals and pinpoints their location within a radius of 21 feet.

Cell phone jammers are already used by prisons in Mexico, France, Australia, and elsewhere. In the U.S., though, phone jamming is illegal (except when done by a federal agency) under a 1934 law that prohibits deliberately interfering with radio signals. A bill that would have allowed prisons to jam cell phone signals was passed by the U.S. Senate in 2009 but died in a House committee. Representative Kevin Brady (R-Tex.) plans to reintroduce a similar measure this spring. “We have the technology to block illegal cell phone calls,” Brady says. “We just need to remove government roadblocks to be able to use it.”

Carriers and wireless industry trade groups oppose prison jamming. They say it would interfere with cell phone communications outside the walls. “In seeking solutions to one problem, we must be careful not to create additional problems that could adversely impact the reliability or dependability of … service,” says Joseph Marx, an AT&T (T) assistant vice-president who works on regulatory issues.

As an alternative, AT&T and others suggest “managed access” technology. Such systems establish a radio-frequency umbrella around a prison that intercepts signals from wireless devices. The system checks each cell phone number to see whether it’s on an approved list. If it’s not, the call is blocked. Since the technology doesn’t interfere with legitimate cell phone calls, it’s not barred by the 1934 law.

Last August the Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman, 130 miles north of Jackson, installed the first such system in the U.S. So far the technology, by Tecore Networks of Columbia, Md., has blocked more than a million attempted calls and texts by inmates while allowing guards and other approved users to make calls, corrections officials say. The state plans to deploy the system at two more prisons this spring. “I’ve searched high and low and I haven’t seen anything better than managed access to deal with illegal cell phones,” says Christopher Epps, commissioner of the Mississippi Corrections Dept. “This is the future for prisons.”

Following the March escape of an inmate who used a smuggled handset to arrange his getaway, the Texas Criminal Justice Dept. is evaluating both managed-access technology and simpler systems that locate cell phones for its 112 prisons. California corrections officials are testing similar systems at two prisons, and they eventually hope to deploy equipment to combat cell phone use by inmates across the state soon. “We’re seeing interest in our technology from prisons all over the country,” says Howard Melamed, chief executive officer of CellAntenna, a Coral Springs (Fla.) company that makes jammers and managed access systems. The company’s gear is being used in Australia, but CellAntenna has yet to make any sales to U.S. prisons.

A big problem, says Melamed, is paying for such systems. Jammers cost more than $30,000 per building, while managed access runs from $400,000 to more than $1 million for a typical prison. ITT Defense’s Cell Hound detection system ranges from about $20,000 for a small facility to $600,000 for a larger prison.

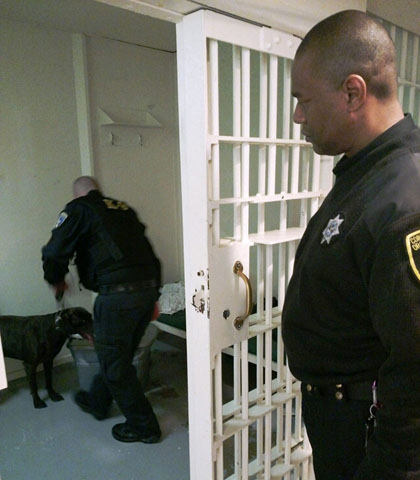

Some jailers prefer lower-tech solutions. Prisons in more than a half-dozen states search for hidden handsets with dogs that can sniff out the chemicals in phone batteries; in Maryland, as word of the dogs has spread among inmates, cell phone seizures have dropped from 1,600 in 2009 to 1,100 last year. And officials at Pelican Bay State Prison in Northern California have confiscated just a dozen or so handsets from inmates since 2006, fewer than any other major prison in the state. Pelican Bay’s remote location, it seems, means the facility suffers from something many outside the walls surely rue: lousy cell phone coverage.

- Blockchain System for Compliant Inmate Transactions - March 4, 2025

- Securus Gets the Signal, Eleven Years Later - August 23, 2024

- Multi-Blockchain System for Inmate Forensics - April 2, 2024