Another article that reinforces the value, to both detainees and their families, of frequent contact and interaction.

Another article that reinforces the value, to both detainees and their families, of frequent contact and interaction.

As the article states, “For children, those meetings were important, she said, because children who have incarcerated parents have a higher risk of becoming teenage parents, dropping out of school, abusing drugs and committing a felony.”

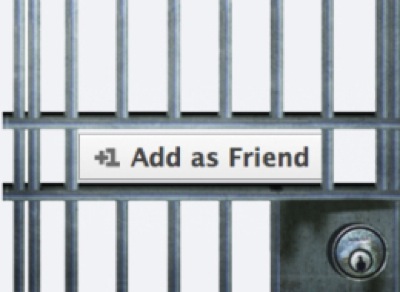

meshDETECT enables more frequent and higher quality conversations between prisoners and their loved ones through the deployment of its secure prison cell phone solution.

Marshae Hunter remembers the close bond she had with her mother when she was a child. But that relationship changed drastically when her mom went to prison.

The times when they baked cookies together, did homework or played with dolls abruptly came to an end. Hunter, who was just 13, was cared for by her grandmother.

But a video visitation program through the Cleveland Eastside Ex-Offender Coalition allowed the family to reopen lines of communication. The program allowed for face-to-face meetings, via video conferencing.

That video program, which helped nearly 200 Northeast Ohio families keep in touch with incarcerated relatives, is gone now.

It ended last fall because of financial troubles.

Experts say its loss created a void that remains unfilled. Children who have a parent or parents behind bars are at greater risk of trouble themselves. Visitation can ease that. And, they say, social visits for inmates while they’re in prison can help lower recidivism rates once they get out.

A state grant that largely funded the coalition’s program, Project IMPACT (Incarcerated Mothers, Parents And Children’s Televisitation) ended last year. The grant was no longer available. The coalition tried to keep the program going, but it accrued a $12,000 deficit, said Caroljean Gates, the coalition’s executive director.

The program, which began in 2004, allowed kids and their relatives to visit through video conferencing with their incarcerated relatives for one hour a week at three Ohio prisons: the Ohio Reformatory for Women in Marysville, Trumbull Correctional Facility in Leavittsburg and the Allen Correctional Facility in Lima. The visits were free to participants.

All the electronic equipment for the prisons and the office was paid for by the coalition.

Gates said she kept the program going as her staff looked for additional funding, but the $1,800 a month it took to pay for a high-speed Internet connection became too expensive. Now the agency is paying back its debt and is at work developing a strategy to restart the program and sustain it.

“We still kept the program going for our clients as we looked for other sources of revenue, but we became overwhelmed,” Gates said. “Our phones have constantly been ringing every week because people want to talk with their loved ones.”

Gates said most of the families who used the video program didn’t have the means to travel long distances to see incarcerated relatives. They also found videoconferencing more convenient than waiting to get on a visitor list at a state prison.

For children, those meetings were important, she said, because children who have incarcerated parents have a higher risk of becoming teenage parents, dropping out of school, abusing drugs and committing a felony.

Not much information exists that shows the number of offenders in state prisons who are parents. A 2010 report by the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction showed that in a sample of 3,396 people, 38 percent of female inmates and 21 percent of males had dependent children living with them at their time of arrest. In a 2004 study about incarcerated fathers, 52 percent of 965 men sampled said they had a minor child.

For Marshae Hunter, now 20, the visits helped her re-establish a connection with her mother, Thomia Hunter, and helped her avoid the same path. When her mother was sentenced to prison in 2006 for murder, Marshae didn’t understand how to process her pain and began to rebel, relatives said. She got into fights at school and struggled academically.

Her grandmother, Vanessa Hunter, said she feared Marshae could someday end up in prison, just like her mother.

“They were very, very close when Thomia went away,” Hunter said. “She was hurt and too young to understand.”

But the ability to talk to her mother made a big difference.

“Being able to see her mom and talk to her eased some of her strain,” Vanessa Hunter said. “We would sit in that room and her mother would tell her the same things I did. We tag- teamed her.”

Marshae Hunter graduated from Shaw High School and now attends Lakeland Community College. She studies early childhood education and works part time for the Downtown Cleveland Alliance as a safety officer.

Since the visitation program was suspended, Hunter still tries to talk with her mother by phone once a week and writes her letters. She said her mother has always encouraged her to follow a positive path.

“I felt like I needed to finish school because if I did well, then she wouldn’t be in there getting down on herself for how I turned out.”

Other participants in the Eastside Ex-Offender Coalition program said it is sorely missed.

Andrea Mudd, 41, of Cleveland, has a 12-year-old daughter with Charles Bibb, who is serving a 15-year sentence at the Allen Correctional Facility in Lima for drug possession and involuntary manslaughter.

Her daughter, Kaylin, an honor-roll student, began to ask about who her father was a few years ago, Mudd said. She last saw him in person when she was 3 years old. Through the video program, she was able to visit a few times a month.

During their visits, Kaylin and her father would play educational games that Kaylin had learned at school, Mudd said. Bibb also talked to Kaylin about his mistakes, and encouraged her to do well in her studies.

“I think the visits were very helpful because now she knows where she came from,” said Mudd, who added that her daughter and the child’s father now write each other.

The visits also help inmates, and Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction officials said they are looking to expand video visitation services at state facilities.

Research shows that offenders who get the social interaction from visits while incarcerated have a lower recidivism rate once they are released from prison, said JoEllen Smith, a spokeswoman for the corrections department.

Smith said the video visitation cuts down on costs for visitors to travel to facilities and for prisons. She said the department would welcome back the Cleveland groups’ program and said the department is looking at how to expand video visitation options at its prisons. Already, the corrections department offers a pay remote visitation service at four prisons.

Gates, a former probation officer, said she believes criminals have to pay their debts to society, but that, for children, the former program helped to establish a much-needed connection with parents. She said she wants to get it back in operation soon.

“When a parent goes to prison it is the child who suffers the most,” Gates said. “No matter who you are or where you come from, as long as a child wasn’t abused, all children deserve to have a relationship with their parents.”

- Multi-Blockchain System for Inmate Forensics - April 2, 2024

- Blockchain to Secure Attorney-Inmate Privacy for Prison Calls - June 28, 2023

- meshDETECT® Announces Grant of Ninth Patent For Blockchain Wireless Services - August 26, 2022